NB COMMENTARY: I really wanted to NOT be in this Beyoncé Madness, but the irony of it all is to see folks being offended by her antics to the point of calling it racist when in fact, if they took the time to read the lyrics, they would see the song is all about Beyoncé getting hers. With a smattering of some retorts against "whatever." The fact that she even uses this "so-called" Black Panther imagery, which in and of itself is a smack in the face of the movement, a downgrade at best in its presentation and surely not militant at all; is amazing to me. The fact that folks are getting hot under the collar over it is outright laughable. Then, on the other hand, you have these drones who support and even consider this "show" as something meaningful or even intrinsically an acknowledgment of her "Blackness." Now I am ROFLMAO and sadly, there are many in that camp as well.

In it's simplicity it barely shows any aggression or hatred or anything against the police. It's a bunch of scantly clad women, fist balled up, dancing with Beyoncé in formation. The directive?? Work hard, grind hard, own it so you can "have the paper." Which none of that was what the BPP Movement was about but surely a capitalistic approach to success.

These folks give money to these movements (Black Lives Matter which is suspect on its face), and bail protesters out of jail, but none of them will give up their way of life to join the Movement on the Real, and that's the point. If twirling her ass, and rocking her crotch gets her money, that is what she will do, she certainly is not on the front lines of the conscious movement or on the front lines of the progressive movement.

Being part of the conscious or progressive movement would be detrimental to her power bank account cause folks would stop spending money on those things that do nothing for their progress and that would mean to stop buying her and her husbands stuff. Her lyrics were more about, "this is what you get for your money, I work hard for it, I slay for it, and see, what your money did for me??? I am at the Super Bowl."

It's all about her and will always be about her, and folks need to get real cause she ain't doing nothing against her handlers who are all "albinos." LOL Check out the lyrics if you haven't already. Click Here for the Lyrics

SOURCE: http://blackpantheressproject.tumblr.com/

Although the Black Panther Party (BPP) revolutionized the condition of Black people and communities in the 1960s, sexism in the group silenced the voices of Black women to promote a Black nationalist agenda that became conflated with the idea of preserving Black masculinity. This project aims to examine how and why this brand of racialized sexism in the Black Panther Party operated in the group, and to shed light on some of the silenced and erased the narratives about radical Black womanhood.

Regina Jennings, a Black woman who joined the Black Panther Party as a teenager, reflects about her experience with sexism in the group. She recounts a particularly difficult encounter with a captain who romantically pursued her. When she rejected his advances, she explains, “he made my life miserable. He gave me ridiculous orders. He shunned me. He found fault in my performance” (262). Ultimately, he had her transferred to a different branch of the organization, even though that meant completely disrupting her way of life. Jennings brought the incidences to the Central Committee’s attention, but the all-male panel accused her of white, bourgeois behaviors and values.

In spite of this situation, Jennings takes great pains not to demonize the entire group. While she and other women in the Black Panther Party confronted this form of sexism and misogyny, they also received a lot of support from Black men. Some Black men even defended Jennings when she complained of the sexual harassment, even when that meant that other men would shame them or call them emasculated. Jennings attributes these circumstances with a lack of knowledge or experience with power. “Black men, who had been too long without some form of power, lacked the background to understand and rework their double standard toward the female cadre” (263), she contends, demonstrating that oppression not only works to degrade a group, but also impels that group to internalize a set of power structures and enact oppression upon others. In spite of her claims, she emphasizes that this type of sexism should not be excused but rather understood. Jennings celebrates the love present in the BPP, forgiving the Party for the conditions that made it imperfect while honoring the uplift it achieved.

“I want you to know how much they perfectly loved you,” she clarifies in reference to those who dedicated their energies to Black communities. “I want you to know that they were willing to die for you” (264).

December 18, 2013

Kathleen Cleaver on Black Natural Hair

Kathleen Cleaver was the first female member of the Black Panther Party’s decision making body. In this interview, Cleaver challenges Euro-centric standards of beauty while expressing the BPP’s stance on self-love, and Black revival through celebrating different images of Blackness. She really does make a case for “the personal is political”!

Although Black women have not always identified with labels such as “feminist,” Black women have advocated for women’s issues as early as the 19th century. Black women have fought for economic justice/equality, against racism, against sexism, and against imperialism throughout U.S. history. In fact, the first wave white feminists learned much of their organizing and political strategies from Black, female abolitionists.

The late 1960s and the 1970s did witness an increasing number of Black women articulating their experience around the words “feminist” or “feminism,” but also a number of Black women challenging the structure of feminist movements. The Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM) took the nation by storm, voicing many women’s grievances, but it did not appeal to many Black women and women of color who interpreted the movement’s work as an agenda that principally furthered white, upper-class women’s issues. Furthermore, many Black women considered their involvement in mixed gender spaces more pressing because they identified more with their male counterparts’ struggles than with the affluent white women’s problems. Kathleen Cleaver explained this phenomenon:

“The problems of Black women and the problems of White women are so completely diverse they cannot possibly be solved in the same type of organization nor met by the same type of activity… [but] I can understand how a White woman cannot relate to a White man.”

This racial solidarity in some ways led some Black women in mixed gender groups to tolerate oppressive ideologies to avoid division, or to subscribe to certain roles. In the pamphlet, “Panther Sisters on Women’s Liberation,” some women insisted that “Black men understand that their manhood is not dependent on keeping Black women subordinate to them,” but also claimed that because “our men have been sort of castrated,” women had to avoid taking up too much space in leadership so that Black men would not have any “fear of women dominating the whole political scene”. That kind of admonition to other Black women invokes ideas about pathologized matriarchy. Other women in the BPP adopted more masculine roles in order to be taken more seriously. Assata Shakur confessed, “You had to develop this whole arrogant kind of macho style in order to be heard… We were just involved in those day to day battles for respect in the Black Panther Party,” revealing the complications in negotiating one’s gender identity and the implications of said gender, even in anti-oppression organizations.

Although the climate of the BPP proved difficult to articulate in terms of gender politics, it was due to Black women’s participation in mixed gender groups and organizations (as opposed to the tendencies of some white, radical feminist groups who championed separatism), that Black women could interrogate the sexist and misogynistic ideologies present in anti-oppression organizations. Various BPP chapters even collaborated with the Women’s Liberation Movement at times, such as in 1969 when WLM members protested the cruel treatment of imprisoned Panther women.

Black women’s presence in the BPP forced men to reconsider their sexist assumptions. Even Party leaders like Eldridge Cleaver shifted positions. In 1968, Cleaver limited Black women’s political potential only to “pussy power,” or, the idea that Black women should withhold sex from Black men until he was ready to “pick up a gun” and embrace his own activism. In contrast, a year later, responding the cruel treatment of Black Panther women in prisons, Cleaver asserted that “if we want to go around and call ourselves a vanguard organization, then we’ve got to be… the vanguard also in the area of women’s liberation, and set an example in that area.” Black women demonstrated that sexist gender norms could not dictate their worth, and that in the grand scheme of things, the police imprisoned them just as they imprisoned Black men, and that white society had stripped them of their femininity just as it had stripped Black men of their masculinity.

Sources:

Anon. “Panther Sisters on Women’s Liberation.” In Heath, ed. Off the Pigs! Pg. 339.

Cleaver, Eldridge. “Message to Sister Erica Hugggins of the Black Panther Party.”The Black Panther Party. 5 July 1969. Reprinted in Foner, The Black Panthers Speak. 98-99.

Cleaver, Eldridge. “Speech to the Nebraska Peace and Freedom Party Convention,” 24 August 1968. Pg. 22

Matthews, Tracye. “No One Ever Asks, What a Man’s Place in the Revolution Is”: Gender and the Politics of The Black Panther Party 1966-1971.” In: The Black Panther Party [Reconsidered]. Edited by Charles E. Jones. Black Classic Press, Baltimore, 1998. Pg. 274, 284, 290.

December 18, 2013

In 1965, then Assistant Secretary of the US Department of Labor, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, issued a report about the question of poverty and the Black American population. Startled by statistics that showed that the unemployment rate of Black people doubled that of white people, Moynihan set out to expose the conditions that economically limited African Americans.

Given its historical context, the Moynihan Report actually represented a radical conceptualization of the relationship between gender identities, family structure, and socio-economic class; however, Moynihan’s statement falls short of the mark by pointing to Black matriarchy as the damning factor. While recognizing that structural conditions that originate in the enslaving of Black people in America has contributed to and caused many of the social disadvantages that plague African American communities contemporarily, Moynihan implicates Black motherhood thereby suggesting that without a patriarchal structure, the Black family is doomed to fail. “He does… identify the fundamental problem confronting the Black community as the ‘tangle of pathology’ associated with a matriarchal family structure,” contest Juan J. Battle and Michael D. Bennet in “African-American Families and Public Policies.” By legitimizing Western, patriarchal culture over non-white alternatives to the family structure, Moynihan prioritizes the suggestion that the Black family is deviant and therefore pathologically damaged instead of demonstrating how institutions like racism, sexism and classism systematically oppress Black families. In this way, he roots the problem in a presumed cultural deficiency, shifting the onus to Black mothers to stop corrupting the family structure instead of on the government to stop discriminating against people of color.

African Americans had initiated conversations about the Black family long before the Moynihan Report; nevertheless, using anecdotal, historical, sociological, and statistical evidence, the Report validated many Black men’s sentiments of “castration” and their resentments about a lost masculinity. Without a doubt, some Black men within the Black Panther Party endorsed the Moynihan Report to sanction their own desires for male superiority. Even Black Panther Party co-founder Huey Newton attested to this male inferiority complex:

“[The Black man] feels that he is something less than a man… Often his wife (who is able to secure a job as a man, cleaning for White people) is the breadwinner. He is therefore, viewed as quiet worthless by his wife and children” (Huey Newton, To Die for the People. Pg. 81)”

Interestingly enough, although Newton does not necessarily subscribe to the subordination of Black women to elevate the Black man, he does not attempt here to undermine the assumption that men should be the breadwinner, that womenshould not head the Black family, or that the solution is to esteem the Black man above the Black woman. Women, especially those in the BPP, would have to create most of the awareness about the fallibility of this form of social change.

Sources:

Battle, Juan J. and Bennet, Michael D. “African-American Families and Public Policy: The Legacy of the Moynihan Report.” Sage Publications, London and New Delhi, 1997. Pg. 154

Moynihan, Daniel P. “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action.” 1965

Newton, H. To Die for the People: The Writings of Huey P. Newton. City Lights Publishers, 2009. Pg. 81

December 18, 2013

In the 1960s, Maulana Karenga spearheaded Us, a Los Angeles-based organization dedicated to raising Black people’s awareness of their cultural heritage. Us propounded the notion that a revival of African traditions would elevate the condition of African Americans. Whether real or contrived, these traditions would ennoble Black people in new ways.

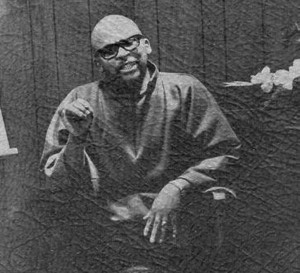

[Malauna Karenga, founder of “Us,” creator of the pan-African/African American Holiday of Kwanzaa, intellectual and writer.]

The Black Panther Party and Us supported each other ideologically, and Maulana Karenga even attended various BPP meetings and rallies. In spite of this initial alliance, the two groups diverged when their ethics no longer aligned. The BPP pushed back against Us’ idea that all Black people were allies in the struggle simply because of the color of their skin. On January 17, 1969, a shootout erupted between BPP and Us members during a Black Student Union meeting at UCLA, which resulted in the death of two BPP members. From that point onward, the relationship between the two organizations never recovered.

Although the Black Panther Party and Us often feuded, the earliest philosophies in the Black Panther Party do reflect many of Karenga’s beliefs. With respect to women, Karenga championed female submission in the name of reinstating Black male authority. He observed:

“What makes a woman appealing is femininity and she can’t be feminine without being submissive. A man has to be a leader and he has to be a man who bases his leadership on knowledge, wisdom, and understanding… The role of the woman is to inspire her man, educate their children and participate in social development. We say male supremacy is based on three things: tradition, acceptance, and reason. Equality is false; it’s the devil’s concept.”

Karenga espoused a complimentary gender theory; this theory depends on the credence that Black women serve to affirm Black men’s superiority. The foundation for this brand of Black racial uplift remains in the notion that empowering Black men necessarily will translate to empower Black communities. Ironically, this philosophy does not interrogate the premise that the restoration of Black male supremacy only occurs insomuch as Black women inspire and educate these Black men. Unfortunately, many of these problematic viewpoints continued to circulate in BPP chapters after Karenga’s departure from the group, necessitating that the Party resolve many of its gendered issues in later years.

Sources:

Halisi, Clyde, ed., The Quotable Karenga. Los Angeles: Us Organization, 1967. Pgs. 27-28

Matthews, Tracye. “No One Ever Asks, What a Man’s Place in the Revolution Is”: Gender and the Politics of The Black Panther Party 1966-1971.” In: The Black Panther Party [Reconsidered]. Edited by Charles E. Jones. Black Classic Press, Baltimore, 1998. Pg. 272

December 18, 2013

How is it that an organization so committed to righting the wrongs committed against Black people, could often support ideologies that endorsed the subordination of women? It is important to recognize that the Black Panther Party (BPP) did not exist in isolation; competing concepts about gender and sexuality perpetuated and upheld in mainstream society shaped the social frameworks of BPP members. The process of dismantling sexism meant theoretical and practical work on the part of all Party members. One female Black Panther who worked in the Oakland and international chapters, the late Connie Matthews assessed the disparity between the BPP’s philosophies and practices.

“I mean, it’s one thing to get up and talk about ideologically you believe this. But you’re asking people to change attitudes and lifestyles overnight, which is not just possible. So I would say tht there was a lot of struggle and there was a lot of male chauvinism… But I would say all in all, in terms of equality… that women had very, very strong leadership roles and were respected as such. It didn’t mean it came automatically.” (Interview with Tracye Matthews, 26 June 1991; Kingston, Jamaica.)

The men and the women in the Black Panther Party had internalized various views that validated sexism and even a racialized form of sexism. This brand of misogyny that specifically targeted Black women (contemporarily referred to as misogynoir) manifested itself in public discourse in two important ways: throughcultural nationalism, and through the Moynihan Report. True equality in the Black Panther Party meant interrogating these cultural “norms” and exchanging those views for a more egalitarian framework.

Source: Matthews, Tracye. “No One Ever Asks, What a Man’s Place in the Revolution Is”: Gender and the Politics of The Black Panther Party 1966-1971.” In:The Black Panther Party [Reconsidered]. Edited by Charles E. Jones. Black Classic Press, Baltimore, 1998. Pg. 289

December 18, 2013

1969, the Free Breakfast for School Children Program was initiated at St. Augustine’s Church in Oakland by the Black Panther Party. The Panthers would cook and serve food to the poor inner city youth of the area.

Male figures in the Black Panther Party, such as Bobby Seale, Huey Newton, and David Hilliard, were key to the initiation process of this project; however, Black women figured greatly in the execution of the first Breakfast Programs. Neighborhood mothers, who lived close to St. Augustine’s Church and actively participated in local parent-teacher associations, focused their energies on the program, even though they were often unaffiliated with the BPP, and made it a success. Female members of the Black Panther Party also contributed to the Free Breakfast Program by feeding as well as educating the children present. Although tensions often arose between the more conservative community mothers — who preferred that the children quietly and orderly ate — and the Black Panther women — who brought their restless, activist spirits into the spaces — these women cooperated to transform their neighborhoods.

Ms. Ruth Beckford, a parishioner at St. Augustine’s Church who helped to establish the Free Breakfast program with Bobby Seale and head of the Church, Father Earl Neal, spoke of the communal uplift that occurred through nourishing the community’s children. “When we were doing it the school principal came down and told us how different the children were. They weren’t falling asleep in class, they weren’t crying with stomach cramps, how alert they were and it was wonderful” (412), Beckford insists in an interview, demonstrating that by feeding the young children, the predominantly female Black Panther Party and Black community members radicalized their youth’s relation to education systems and thus their youth’s access to societal opportunities. The Free Breakfast Program, a largely woman-run project, asserted Black people’s right to food, to preparations so that they could thrive academically, and to conditions to further their position in society.

Source: Heynen, Nik. “Bending the Bars of Empire from Every Ghetto for Survival: The Black Panther Party’s Radical Antihunger Politics of Social Reproduction and Scale.” Department of Geography, University of Georgia, published online: May 2009.

December 17, 2013

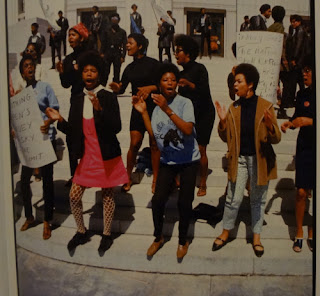

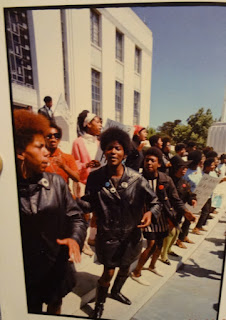

Women of the Black Panther Party demonstrating in front of Alameda County Courthouse Oakland, CA

|  |

Taken from “Black Panthers: 1968” by Howard L. Bingham

December 17, 2013

“[W]omen ran the BPP pretty much. I don’t now how it got to be a male’s party or thought of as being a male’s party. Because those things, when you really look at it in terms of society, those things are looked on as being woman things, you know, feeding children, taking care of the sick and uh, so. Yeah, we did that. We actually ran the BPP’s programs.” (Frankye Malika Adams in an interview with Tracye Matthews, 29 September 1994; Harlem, New York)

When the media invokes images of the Black Panther Party (BPP), it often displays images of gun-toting Black men in military garb. Historical representations have relegated many women who participated in and devoted their energies to the Black Panther Party to a prop status. Excluding the outliers like Assata Shakur and Kathleen Cleaver, women in the Black Panther Party earn their time in the spotlight insomuch as they endorse the male cause; even some of the more famous images of these Black women feature them holding up signs for the Free Huey Campaign. Despite these depictions, Black women played a fundamental role in the Black Panther Party. Often comprising the majority of local BPP groups, women staffed and coordinated free breakfast programs, liberation schools, and medical clinics. The Party even sought out Black women unaffiliated with the organization, such as women on welfare, grandmothers and community figures, to staff these initiatives. If these women played such a fundamental role in the infrastructure of the BPP, why aren’t Black women as celebrated for their contributions? History has a way of degrading work that mirrors “traditional” female duties to categories like “community service” or “support work”. The term “support work,” especially invokes the connotation of inferior, menial and subordinate labor. Sexism not only impacted what jobs Black women in the BPP received or fulfilled but also how history conveys the value of said efforts.

Source: Matthews, Tracye. “No One Ever Asks, What a Man’s Place in the Revolution Is”: Gender and the Politics of The Black Panther Party 1966-1971.” In:The Black Panther Party [Reconsidered]. Edited by Charles E. Jones. Black Classic Press, Baltimore, 1998.

December 17, 2013

“Black liberation politics became equated with black men’s attempts to regain their manhood at the expense of black women,” asserts Anita Simmons in the chapter “Black Womanhood, Misogyny and Hip-Hop Culture: A Feminist Intervention”. Simmons continues, “In the Black Panther Party, attainment of black manhood meant the degradation of black women and womanhood.” Sexism in the Black Panther Party (BPP) silenced the voices of Black women to promote a Black nationalist agenda that became conflated with the idea of preserving Black masculinity. This project aims to examine how this brand of racialized sexism in the Black Panther Party silenced and even erased the narratives about radical Black womanhood in the late 1960s from our social history. What are these narratives? How did women in the Black Panther Party radicalize their position? This project will also examine the interaction between Black feminists of the 1970s and their criticism of Black men’s understanding of Black womanhood. What was the stance of women in the Black Panther Party? Were there Black feminists who were also Black Panthers?

ABOUT

Although the Black Panther Party (BPP) revolutionized the condition of Black people and communities in the 1960s, sexism in the group silenced the voices of Black women to promote a Black nationalist agenda that became conflated with the idea of preserving Black masculinity. This project aims to examine how and why this brand of racialized sexism in the Black Panther Party operated in the group, and to shed light on some of the silenced and erased the narratives about radical Black womanhood.

Comments