I think what Black Arts did was inspire a whole lot of Black people to write. Moreover, there would be no multiculturalism movement without Black Arts. Latinos, Asian Americans, and others all say they began writing as a result of the example of the 1960s. Blacks gave the example that you don't have to assimilate. You could do your own thing, get into your own background, your own history, your own tradition and your own culture. I think the challenge is for cultural sovereignty and Black Arts struck a blow for that.--Ishmael Reed

If we had not had a Black Arts movement in the sixties we certainly wouldn't have had national Black literary figures like Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Alice Walker, or Toni Morrison because much more so than the Harlem Renaissance, in which Black artists were always on the leash of white patrons and publishing houses, the Black Arts movement did it for itself. What you had was Black people going out nationally, in mass, saying that we are an independent Black people and this is what we produce.

--Robert Chrisman, founding editor, Black Scholar Magazine

graphics by Adam Turner, Black Bird Productions

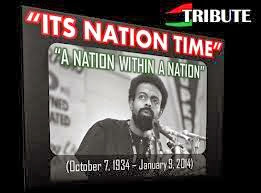

Seven years ago, in a Time magazine issue devoted to contemporary African-American culture, Henry Louis Gates declared the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s the shortest and least successful African-American literary renaissance. Gates's comments are unfortunate and ironic; the formation of Black Studies programs, changes in curricula, and the affirmative hiring of African-American faculty in humanities departments across the US during the late 1970s and 1980s were due, in significant part, to the militance of Black Arts artists, writers, performers, and critics and the conceptual power of the "Black Aesthetic."

Though Gates's The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism (Oxford, 1988) and Houston A. Baker's Blues, Ideology, and Afro-American Literature: A Vernacular Theory (University of Chicago, 1984) show the influence of the Black Aesthetic, not since Stephen Henderson's Understanding the New Black Poetry: Black Speech and Black Music as Poetic References (William Morrow, 1973) has a critic openly admitted the theoretical and practical importance of the movement. Needless to say, it has been just as long since a book affirmed the importance of performance to the movement. In part this silence is due to Larry Neal's untimely death in 1980, a death that denied the Black Aesthetic a forceful voice in the upper echelons of academic discourse.

Fortunately, Neal's student, Kimberly W. Benston, affords an important opening for the burgeoning conversation about the Black Arts Movement (BAM) that has picked up in recent years, a conversation further energized by Kalamu Ya Salaam's forthcoming The Magic of Juju: An Appreciation of the Black Arts Movement (Third World Press). Most importantly, Benston's book anchors the conversation to performance. Though he pays careful attention to texts such as drama, music, poetry, sermons, criticism, and autobiography, the focus is always on their performativity.

--Mike Sell, from a review of Performing Blackness: Enactments of African-American Modernism. By Kimberly W. Benston. London: Routledge, 2000; pp. 400.

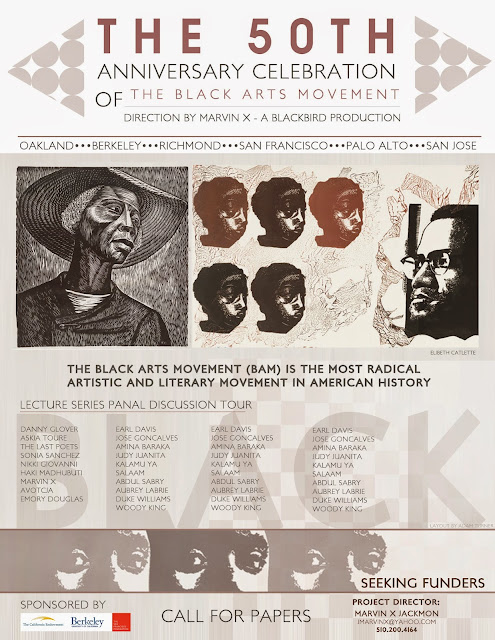

Join the San Francisco Bay Area BAM Revolution, 2015

photo Necola Adams/graphics Kalamu Chache'

The following persons have joined the Bay Area BAM Revolution, 2015

Kweli Tutashinda, Wellness

Elliott Savoy Bey, Music therapy

Malaika Kambon, Media team

Dr. Kofi Harris, Political affairs

Michael James Satchell, Moorish History

Duane Deterville, Visual Arts

Renee Portis, PR

Necola Adams, PR

Renaldo Ricketts, visual artist

Paul Tillman, musician

Roger Smith, educator

Fuad Satterfield, visual artist

Malik Seneferu, visual artist

Wish List

Sincere people of spiritual consciousness

Generous funds to produce a first class festival/conference

Video cameras

Transportation vehicles

Permanent housing for conscious artists, especially the BAM elders

PR team to get the word out throughout the BAY AREA

Young artists in the BAM tradition (art for revolution)

Spread the word

In the BAM tradition, this should be a self supporting project:

PLEASE SEND A GENEROUS DONATION TO

BAY AREA BAM 2015

339 Lester Ave. #10

Oakland CA 94606

510-200-4164

jmarvinx@yahoo.com

Negro es bello/Black is beautiful by Elizabeth Catlett Mora

Many of the Black Arts Movement’s leading artists, including Ed Bullins, Nikki Giovanni, Woodie King, Haki Madhubuti, Sonia Sanchez, Askia Touré, Marvin X and Val Gray Ward, remain artistically productive today. Its influence can also be seen in the work of later artists, from the writers Toni Morrison, John Edgar Wideman, and August Wilson to actors Avery Brooks, Danny Glover, and Samuel L. Jackson, to hip-hop artists Mos Def, Talib Kweli, and Chuck D.

Kaluma ya Salaam on the Black Arts Movement Both inherently and overtly political in content, the Black Arts movement was the only American literary movement to advance "social engagement" as a sine qua non of its aesthetic. The movement broke from the immediate past of protest and petition (civil rights) literature and dashed forward toward an alternative that initially seemed unthinkable and unobtainable: Black Power.

In a 1968 essay, "The Black Arts Movement," Larry Neal proclaimed Black Arts the "aesthetic and spiritual sister of the Black Power concept." As a political phrase, Black Power had earlier been used by Richard Wright to describe the mid-1950s emergence of independent African nations. The 1960s' use of the term originated in 1966 with Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee civil rights workers Stokely Carmichael and Willie Ricks. Quickly adopted in the North, Black Power was associated with a militant advocacy of armed self-defense, separation from "racist American domination," and pride in and assertion of the goodness and beauty of Blackness.

Although often criticized as sexist, homophobic, and racially exclusive (i.e., reverse racist), Black Arts was much broader than any of its limitations. Ishmael Reed, who is considered neither a movement apologist nor advocate ("I wasn't invited to participate because I was considered an integrationist"), notes in a 1995 interview,

I think what Black Arts did was inspire a whole lot of Black people to write. Moreover, there would be no multiculturalism movement without Black Arts. Latinos, Asian Americans, and others all say they began writing as a result of the example of the 1960s. Blacks gave the example that you don't have to assimilate. You could do your own thing, get into your own background, your own history, your own tradition and your own culture. I think the challenge is for cultural sovereignty and Black Arts struck a blow for that.

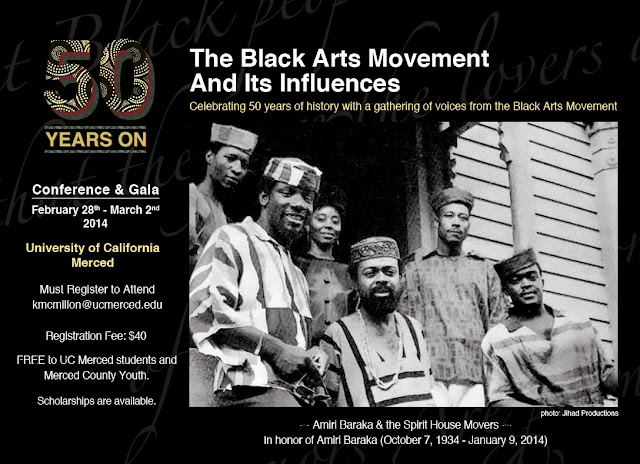

History and Context. The Black Arts movement, usually referred to as a "sixties" movement, coalesced in 1965 and broke apart around 1975/1976. In March 1965 following the 21 February assassination of Malcolm X, LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka) moved from Manhattan's Lower East Side (he had already moved away from Greenwich Village) uptown to Harlem, an exodus considered the symbolic birth of the Black Arts movement. Jones was a highly visible publisher (Yugen and Floating Bear magazines, Totem Press), a celebrated poet (Preface to a Twenty-Volume Suicide Note, 1961, and The Dead Lecturer, 1964), a major music critic (Blues People, 1963), and an Obie Award-winning playwright (Dutchman, 1964) who, up until that fateful split, had functioned in an integrated world. Other than James Baldwin, who at that time had been closely associated with the civil rights movement, Jones was the most respected and most widely published Black writer of his generation.

While Jones's 1965 move uptown to found the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School (BARTS) is the formal beginning (it was Jones who came up with the name "Black Arts"), Black Arts, as a literary movement, had its roots in groups such as the Umbra Workshop. Umbra (1962) was a collective of young Black writers based in Manhattan's Lower East Side; major members were writers Steve Cannon, Tom Dent, Al Haynes, David Henderson, Calvin C. Hernton, Joe Johnson, Norman Pritchard, Lenox Raphael, Ishmael Reed, Lorenzo Thomas, James Thompson, Askia M. Touré (Roland Snellings; also a visual artist), Brenda Walcott, and musician-writer Archie Shepp. Touré, a major shaper of "cultural nationalism," directly influenced Jones. Along with Umbra writer Charles Patterson and Charles's brother, William Patterson, Touré joined Jones, Steve Young, and others at BARTS.

Umbra, which produced Umbra Magazine, was the first post-civil rights Black literary group to make an impact as radical in the sense of establishing their own voice distinct from, and sometimes at odds with, the prevailing white literary establishment. The attempt to merge a Black-oriented activist thrust with a primarily artistic orientation produced a classic split in Umbra between those who wanted to be activists and those who thought of themselves as primarily writers, though to some extent all members shared both views. Black writers have always had to face the issue of whether their work was primarily political or aesthetic. Moreover, Umbra itself had evolved out of similar circumstances: In 1960 a Black nationalist literary organization, On Guard for Freedom, had been founded on the Lower East Side by Calvin Hicks. Its members included Nannie and Walter Bowe, Harold Cruse (who was then working on Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, 1967), Tom Dent, Rosa Guy, Joe Johnson, LeRoi Jones, and Sarah Wright, among others. On Guard was active in a famous protest at the United Nations of the American-sponsored Bay of Pigs Cuban invasion and was active in support of the Congolese liberation leader Patrice Lumumba. From On Guard, Dent, Johnson, and Walcott along with Hernton, Henderson, and Touré established Umbra.

Another formation of Black writers at that time was the Harlem Writers Guild, led by John O. Killens, which included Maya Angelou, Jean Carey Bond, Rosa Guy, and Sarah Wright among others. But the Harlem Writers Guild focused on prose, primarily fiction, which did not have the mass appeal of poetry performed in the dynamic vernacular of the time. Poems could be built around anthems, chants, and political slogans, and thereby used in organizing work, which was not generally the case with novels and short stories. Moreover, the poets could and did publish themselves, whereas greater resources were needed to publish fiction. That Umbra was primarily poetry- and performance-oriented established a significant and classic characteristic of the movement's aesthetics.

When Umbra split up, some members, led by Askia Touré and Al Haynes, moved to Harlem in late 1964 and formed the nationalist-oriented "Uptown Writers Movement," which included poets Yusef Rahman, Keorapetse "Willie" Kgositsile from South Africa, and Larry Neal. Accompanied by young "New Music" musicians, they performed poetry all over Harlem. Members of this group joined LeRoi Jones in founding BARTS.

Jones's move to Harlem was short-lived. In December 1965 he returned to his home, Newark (N.J.), and left BARTS in serious disarray. BARTS failed but the Black Arts center concept was irrepressible mainly because the Black Arts movement was so closely aligned with the then-burgeoning Black Power movement.

The mid- to late 1960s was a period of intense revolutionary ferment. Beginning in 1964, rebellions in Harlem and Rochester, New York, initiated four years of long hot summers. Watts, Detroit, Newark, Cleveland, and many other cities went up in flames, culminating in nationwide explosions of resentment and anger following Martin Luther King, Jr.'s April 1968 assassination.

In his seminal 1965 poem "Black Art," which quickly became the major poetic manifesto of the Black Arts literary movement, Jones declaimed "we want poems that kill." He was not simply speaking metaphorically. During that period armed self-defense and slogans such as "Arm yourself or harm yourself' established a social climate that promoted confrontation with the white power structure, especially the police (e.g., "Off the pigs"). Indeed, Amiri Baraka (Jones changed his name in 1967) had been arrested and convicted (later overturned on appeal) on a gun possession charge during the 1967 Newark rebellion. Additionally, armed struggle was widely viewed as not only a legitimate, but often as the only effective means of liberation. Black Arts' dynamism, impact, and effectiveness are a direct result of its partisan nature and advocacy of artistic and political freedom "by any means necessary." America had never experienced such a militant artistic movement.

Nathan Hare, the author of The Black Anglo-Saxons (1965), was the founder of 1960s Black Studies. Expelled from Howard University, Hare moved to San Francisco State University where the battle to establish a Black Studies department was waged during a five-month strike during the 1968-1969 school year. As with the establishment of Black Arts, which included a range of forces, there was broad activity in the Bay Area around Black Studies, including efforts led by poet and professor Sarah Webster Fabio at Merrit College.

The initial thrust of Black Arts ideological development came from the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM), a national organization with a strong presence in New York City. Both Touré and Neal were members of RAM. After RAM, the major ideological force shaping the Black Arts movement was the US (as opposed to "them') organization led by Maulana Karenga. Also ideologically important was Elijah Muhammad's Chicago-based Nation of Islam.

These three formations provided both style and ideological direction for Black Arts artists, including those who were not members of these or any other political organization. Although the Black Arts movement is often considered a New York-based movement, two of its three major forces were located outside New York City.

BAM BAY AREA

As the movement matured, the two major locations of Black Arts' ideological leadership, particularly for literary work, were California's Bay Area because of Black Dialogue magazine, the Journal of Black Poetry and the Black Scholar, and the Chicago-Detroit axis because of Negro Digest/Black World and Third World Press in Chicago, and Broadside Press and Naomi Long Madgett's Lotus Press in Detroit. The only major Black Arts literary publications to come out of New York were the short-lived (six issues between 1969 and 1972) Black Theatre magazine published by the New Lafayette Theatre and Black Dialogue, which had actually started in San Francisco (1964-1968) and relocated to New York (1969-1972).

In 1967 LeRoi Jones visited Karenga in Los Angeles and became an advocate of Karenga's philosophy of Kawaida. Kawaida, which produced the "Nguzo Saba" (seven principles), Kwanzaa, and an emphasis on African names, was a multifaceted, categorized activist philosophy. Jones also met Bobby Seale and Eldridge Cleaver and worked with a number of the founding members of the Black Panthers. Additionally, Askia Touré was a visiting professor at San Francisco State and was to become a leading (and long lasting) poet as well as, arguably, the most influential poet-professor in the Black Arts movement. Playwright Ed Bullins and poet Marvin X had established Black Arts West, and Dingane Joe Goncalves had founded the Journal of Black Poetry (1966). This grouping of Ed Bullins, Dingane Joe Goncalves, LeRoi Jones, Sonia Sanchez, Askia M. Touré, and Marvin X became a major nucleus of Black Arts leadership.

BAM BAY AREA

Theory and Practice. The two hallmarks of Black Arts activity were the development of Black theater groups and Black poetry performances and journals, and both had close ties to community organizations and issues. Black theaters served as the focus of poetry, dance, and music performances in addition to formal and ritual drama. Black theaters were also venues for community meetings, lectures, study groups, and film screenings. The summer of 1968 issue of Drama Review, a special on Black theater edited by Ed Bullins, literally became a Black Arts textbook that featured essays and plays by most of the major movers: Larry Neal, Ben Caldwell, LeRoi Jones, Jimmy Garrett, John O'Neal, Sonia Sanchez, Marvin X, Ron Milner, Woodie King, Jr., Bill Gunn, Ed Bullins, and Adam David Miller. Black Arts theater proudly emphasized its activist roots and orientations in distinct, and often antagonistic, contradiction to traditional theaters, both Black and white, which were either commercial or strictly artistic in focus.

By 1970 Black Arts theaters and cultural centers were active throughout America. The New Lafayette Theatre (Bob Macbeth, executive director, and Ed Bullins, writer in residence) and Barbara Ann Teer's National Black Theatre led the way in New York, Baraka's Spirit House Movers held forth in Newark and traveled up and down the East Coast. The Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC) and Val Grey Ward's Kuumba Theatre Company were leading forces in Chicago, from where emerged a host of writers, artists, and musicians including the OBAC visual artist collective whose "Wall of Respect" inspired the national community-based public murals movement and led to the formation of Afri-Cobra (the African Commune of Bad, Revolutionary Artists). There was David Rambeau's Concept East and Ron Milner and Woodie King’s Black Arts Midwest, both based in Detroit. Ron Milner became the Black Arts movement's most enduring playwright and Woodie King became its leading theater impresario when he moved to New York City. In Los Angeles there was the Ebony Showcase, Inner City Repertory Company, and the Performing Arts Society of Los Angeles (PALSA) led by Vantile Whitfield. In San Francisco was the aforementioned Black Arts West. BLKARTSOUTH (led by Tom Dent and Kalamu ya Salaam) was an outgrowth of the Free Southern Theatre in New Orleans and was instrumental in encouraging Black theater development across the south from the Theatre of Afro Arts in Miami, Florida, to Sudan Arts Southwest in Houston, Texas, through an organization called the Southern Black Cultural Alliance. In addition to formal Black theater repertory companies in numerous other cities, there were literally hundreds of Black Arts community and campus theater groups.

A major reason for the widespread dissemination and adoption of Black Arts was the development of nationally distributed magazines that printed manifestos and critiques in addition to offering publishing opportunities for a proliferation of young writers. Whether establishment or independent, Black or white, most literary publications rejected Black Arts writers. The movement's first literary expressions in the early 1960s came through two New York-based, nationally distributed magazines, Freedomways and Liberator. Freedomways, "a journal of the Freedom Movement," backed by leftists, was receptive to young Black writers. The more important magazine was Dan Watts's Liberator, which openly aligned itself with both domestic and international revolutionary movements. Many of the early writings of critical Black Arts voices are found in Liberator. Neither of these were primarily literary journals.

BAM BAY AREA

The first major Black Arts literary publication was the California-based Black Dialogue (1964), edited by Arthur A. Sheridan, Abdul Karim, Edward Spriggs, Aubrey Labrie, and Marvin Jackmon (Marvin X). Black Dialogue was paralleled by Soulbook (1964), edited by Mamadou Lumumba (Kenn Freeman) and Bobb Hamilton. Oakland-based Soulbook was mainly political but included poetry in a section ironically titled "Reject Notes."

Dingane Joe Goncalves became Black Dialogue's poetry editor and, as more and more poetry poured in, he conceived of starting the Journal of Black Poetry. Founded in San Francisco, the first issue was a small magazine with mimeographed pages and a lithographed cover. Up through the summer of 1975, the Journal published nineteen issues and grew to over one hundred pages. Publishing a broad range of more than five hundred poets, its editorial policy was eclectic. Special issues were given to guest editors who included Ahmed Alhamisi, Don L. Lee (Haki R. Madhubuti), Clarence Major, Larry Neal, Dudley Randall, Ed Spriggs, Marvin X and Askia Touré. In addition to African Americans, African, Caribbean, Asian, and other international revolutionary poets were presented.

Founded in 1969 by Nathan Hare and Robert Chrisman, the Black Scholar, "the first journal of black studies and research in this country," was theoretically critical. Major African-disasporan and African theorists were represented in its pages. In a 1995 interview Chrisman attributed much of what exists today to the groundwork laid by the Black Arts movement:

If we had not had a Black Arts movement in the sixties we certainly wouldn't have had national Black literary figures like Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Alice Walker, or Toni Morrison because much more so than the Harlem Renaissance, in which Black artists were always on the leash of white patrons and publishing houses, the Black Arts movement did it for itself. What you had was Black people going out nationally, in mass, saying that we are an independent Black people and this is what we produce.

For the publication of Black Arts creative literature, no magazine was more important than the Chicago-based Johnson publication Negro Digest / Black World. Johnson published America's most popular Black magazines, Jet and Ebony. Hoyt Fuller, who became the editor in 1961, was a Black intellectual with near-encyclopedic knowledge of Black literature and seemingly inexhaustible contacts. Because Negro Digest, a monthly, ninety-eight-page journal, was a Johnson publication, it was sold on newsstands nationwide. Originally patterned on Reader’s Digest, Negro Digest changed its name to Black World in 1970, indicative of Fuller’s view that the magazine ought to be a voice for Black people everywhere. The name change also reflected the widespread rejection of "Negro" and the adoption of "Black" as the designation of choice for people of African descent and to indicate identification with both the diaspora and Africa. The legitimation of "Black" and "African" is another enduring legacy of the Black Arts movement.

Negro Digest / Black World published both a high volume and an impressive range of poetry, fiction, criticism, drama, reviews, reportage, and theoretical articles. A consistent highlight was Fuller's perceptive column Perspectives ("Notes on books, writers, artists and the arts") which informed readers of new publications, upcoming cultural events and conferences, and also provided succinct coverage of major literary developments. Fuller produced annual poetry, drama, and fiction issues, sponsored literary contests, and gave out literary awards. Fuller published a variety of viewpoints but always insisted on editorial excellence and thus made Negro Digest / Black World a first-rate literary publication. Johnson decided to cease publication of Black World in April 1976: allegedly in response to a threatened withdrawal of advertisement from all of Johnson's publications because of pro-Palestinian/anti-Zionist articles in Black World.

The two major Black Arts presses were poet Dudley Randall's Broadside Press in Detroit and Haki Madhubuti's Third World Press in Chicago. From a literary standpoint, Broadside Press, which concentrated almost exclusively on poetry, was by far the more important. Founded in 1965, Broadside published more than four hundred poets in more than one hundred books or recordings and was singularly responsible for presenting older Black poets (Gwendolyn Brooks, Sterling A. Brown, and Margaret Walker) to a new audience and introducing emerging poets (Nikki Giovanni, Etheridge Knight, Don L. Lee/Haki Madhubuti, Marvin X and Sonia Sanchez) who would go on to become major voices for the movement. In 1976, strapped by economic restrictions and with a severely overworked and overwhelmed three-person staff, Broadside Press went into serious decline. Although it functions mainly on its back catalog, Broadside Press is still alive.

While a number of poets (e.g., Amiri Baraka, Nikki Giovanni, Haki Madhubuti, Marvin X and Sonia Sanchez), playwrights (e.g., Ed Bullins and Ron Milner), and spoken-word artists (e.g., the Last Poets and Gil Scott-Heron, both of whom were extremely popular and influential although often overlooked by literary critics) are indelibly associated with the Black Arts movement, rather than focusing on their individual work, one gets a much stronger and much more accurate impression of the movement by reading seven anthologies focusing on the 1960s and the 1970s.

Black Fire (1968), edited by Baraka and Neal, is a massive collection of essays, poetry, fiction, and drama featuring the first wave of Black Arts writers and thinkers. Because of its impressive breadth, Black Fire stands as a definitive movement anthology.

For Malcolm X, Poems on the Life and the Death of Malcolm X (1969), edited by Dudley Randall and Margaret Taylor Goss Burroughs, demonstrates the political thrust of the movement and the specific influence of Malcolm X. There is no comparable anthology in American poetry that focuses on a political figure as poetic inspiration.

The Black Woman (1970), edited by Toni Cade Bambara, is the first major Black feminist anthology and features work by Jean Bond, Nikki Giovanni, Abbey Lincoln, Audre Lorde, Paule Marshall, Gwen Patton, Pat Robinson, Alice Walker, Shirley Williams, and others.....

Comments