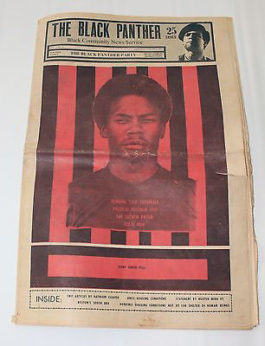

CAPTURED OVER 52 YEARS AGO BACK IN 1969 AT THE AGE OF 21; THE LONGEST U.S. GOVERNMENT HELD

VETERAN BLACK PANTHER POLITICAL PRISONER, COMRADE ROMAINE "CHIP" FITZGERALD, HAS JUST

JOINED THE ANCESTORS. IN 13 DAYS ON APRIL 11TH HE WOULD HAVE BEEN 73 YEARS OLD.

FREE OUR ELDER FREEDOM FIGHTERS NOW!

ROMAINE “CHIP” FITZGERALD BIOGRAPHY

Romaine Fitzgerald was born April 11, 1949. His father, Leon Thayer Fitzgerald, was born in Oklahoma and his mother, Marie Russell, was born in Shreveport, Louisiana. His parents met in Los Angeles, married, bought a home, and started a family in the Watts/Willowbrook community of Los Angeles, one of the poorest neighborhoods in the area. Romaine was the youngest of four siblings and they all provided him with an abundance of love and encouragement. Romaine’s father often took Chip and his two older sisters and older brother on camping trips to the mountains and lakes not far from where they lived.

Romaine's mother Marie was employed as a domestic worker. At home, Mrs. Fitzgerald enjoyed working in the flower beds and vegetable garden, as well as knitting and crocheting. With these skills she made a lot of her children's clothing and provided fresh produce for the family. Romaine's father Leon worked for the city of Los Angeles in the Department of Water and Power and in his spare time, enjoyed hunting and fishing. Growing up in the poverty stricken enclaves of Watts and Compton, Romaine remembered that his parents worked very hard to make ends meet. Nevertheless, the couple struggled, and by the time Romaine turned five, they had divorced. His mother won custody of the children and took on the added responsibility of leading a household alone. A proud woman who wanted to set a good example for her children, Ms. Fitzgerald refused to accept county or state welfare. Instead, she supplemented her domestic job as a dishwasher at the Statler Hotel and by taking on additional domestic work in the homes wealthy people in Beverly Hills and the Wilshire District. Unable to properly supervise her children because she worked multiple jobs, Ms. Fitzgerald’s frequent absences from home made it easy for Romaine to get involved in mischievous activities, including committing petty larceny and associating with the area’s local gang members. Because his siblings could not properly supervise him while his mother worked multiple jobs, Chip often made friends with the homeless youth in his neighborhood, and together they sought out mischief wherever they could find it.

Romaine attended grammar school at Lincoln Elementary and middle school at Ralph J. Bunch Jr. High School. He was also a participant in the Boys Club of America. Despite trying his best to be a good student, he was drawn to the streets and slowly slipped deeper into criminality. Though his mother attempted to steer Romaine in a more positive direction by sending him to live with his father in Compton, Romaine’s attraction and deep affinity for the street life drew him back to his friends in Watts. This desire to live by his wits landed Romaine in Juvenile Hall and California Youth Authority (CYA) reform schools on several occasions. Eventually his petty crimes caught up with him and he subsequently spent two years at DVI, a CYA and adult prison. Spending most of his time in solitary confinement, Chip decided to take up reading and he ultimately became aware of the Black freedom struggle unfolding in the United States.

It was the mid-sixties and the world seemed on fire with activism. Having had considerable contact with prisoners who had formed reading groups and subsequently read extensively about the Black movement, Chip quickly developed a sense of the importance of Black history and Black culture and of the long term impact of racism on the Black community. In 1967, while serving time for a residential robbery, Chip encountered literature about the Black Panther Party and decided to investigate further. He and scores of other prisoners immediately noticed the Party’s desire to struggle for Black freedom and they were outraged to discover that racism was the result of ignorance and greed. He also began to understand how capitalism undermined the legitimate demands of people seeking freedom and justice. Heartened by what he learned, Chip took himself through a process of reevaluation and concluded he no longer aspired to be involved in criminal activity. Instead, he made the decision to devote his life to the freedom struggle and to the ideals for which organizations like the Black Panther Party stood. Upon his release from jail in early 1969, he and a group of fellow prisoners from DVI, joined the Southern California Chapter of the Black Panther Party. Like many young people during the turbulent 1960's, Romaine was rescued from a potential life of criminality and became politically active by serving his community. Chip made the conscious choice to devote his life to the Black freedom movement. Tired of seeing racism prevent poor and oppressed people from exercising their human right to self-determination, Chip enthusiastically delved into community work assigned him by local Black Panther Party leaders. From education and housing initiatives to selling the Black Panther Party newspaper and serving poor kid’s free breakfasts, he became enthralled with the positive work of refashioning his community from one that was oppressed, excluded and subservient to one that was self-determining and self-sufficient. Ms. Fitzgerald often reflected on what a positive change her son had gone through after seeing him develop a serious interest in participating in the Civil Rights Movement.

Bruce Richard, a union executive who in 1969 joined the Black Panther Party's Southern California Chapter with Chip, recalled that, “Upon Chip's release from jail, he wasted no time joining the Black Panther Party. Chip worked tirelessly in various capacities in the Westside office of the Chapter. To be a Panther was a 24/7 commitment, and every single day seemed like weeks due to the volume of activities during that explosive period. Chip was totally consumed by his work in the Party's Free Breakfast Program, the tutorial program, selling Panther papers, attending political education classes and distributing leaflets throughout the community that explained the philosophy and objectives of the Black Panther Party. He was a favorite of many in the communities we served. The children especially loved him, as was often reflected in their smiling little faces when he appeared.”

Like many BPP members, Chip learned the principles of socialism, the importance of organizational discipline, and the proper handling and use firearms. Erroneously thinking the BPP would lead the revolution that saved Black people from lives of endless oppression, he identified with the ideology of armed struggle. To this end, his activities landed him in deep trouble when Officer Leslie Clapp, a California Highway Patrolmen, stopped him and two other Panthers as they drove across town to expropriate funds for what they hoped would be the impending revolution. A heated conversation with the highway patrolman quickly escalated into an armed confrontation and before long, Officer Clapp lay on the ground gravely wounded and Chip bled profusely from a gunshot wound to the head. Though they fled the scene, Chip’s co-passengers were arrested the following day and state subsequently tried, convicted, and sentenced them to prison.

Chip managed to remain at large for several weeks until his arrest for the September 1969 killing of a Los Angeles-area security guard. Two weeks after this incident, the police located and arrested Chip, who at the time still wore the bandage from having been shot by the California Highway Patrolman. The state of California tried and convicted him for his role in Officer Clapp’s assault and for the murder of security guard Barge Miller, who Chip shot during an altercation at a neighborhood shopping center. During this fatal incident, Chip was intervening in an ongoing armed confrontation between the security guard and another member of the Black Panther Party. He’d heard shooting and came to his friend’s rescue. Though Chip had been 19-years-old only months before his arrest, by the time the court sentenced him to death, he was 20. Within a few years, the state of California ruled the death penalty unconstitutional and relocated Chip from San Quentin’s Death Row to that prison’s now infamous Adjustment Center. According to California law, Chip became eligible for parole in 1976, after having served 7 years of his prison term.

Saddened by having participated in taking the life of another human being, Chip entered a deep depression from his feelings of shame and sorrow, which emanated from what he knew was the pain he had caused his victims and the families of his victims. Managing to maintain a façade of strength for those inside and outside of prison, Chip’s reality was that he struggled with frequent nightmares of both shooting incidents and often woke up in the middle of the night in cold sweats. He explained to the parole board that after he realized he had taken the life of an innocent man and permanently maimed another, that he felt sorry for the irreversible pain he had caused them and their families and was ashamed of how he had lived his life up to that point.

Though numerous prison groups attempted to recruit Chip to their organizations, he had decided to avoid all avenues of trouble. With a deep and abiding awareness of his hurtful actions, Chip gave San Quentin’s warden his solemn word that he “would not become involved in illegal activity.” Also, before being granted a prison job as an Administration Office Clerk, Chip passed a rigorous polygraph test to confirm that he was not affiliated with any prison gangs or engaged in other illicit activities. During this period, he informed the parole board that he was far from proud of his crimes and lamented the fact that he had caused his family heartache and shame. Indeed, his actions and subsequent prison sentence led to his mother having a nervous breakdown and he knew he had to do something when the doctor informed his family that her mental collapse had been precipitated by her worry and grief over her youngest son’s incarceration.

Chip later turned to the prison psychiatrist for help, and over time, her counseling convinced him that only he could overcome his feelings of guilt and self-hate and only he could rebuild his self-esteem and turn his life around. Having engaged in the hard work of making such a positive change, prison authorities transferred Chip to Vacaville Prison to participate in special programs that helped prisoners better understand themselves and their antisocial behavior. Experiencing positive gains during his 18-month stay at Vacaville, Chip made a successful break away from his criminal past. He understood that his anti-social behavior had derived from his human desire to be loved and respected. It was during this process that Chip realized how poverty and the breakup of his parents had left him vulnerable. Chip could see clearly how and why he had descended into a life littered with poor choices. Though to reach this point, he had to experience the deprivations and difficulties of prison, including being stabbed by a member of a white racist prison gang, Chip ultimately turned his life around and evolved into a more caring and loving human being.

During his half century of imprisonment, Romaine has taken college courses that range from anthropology, environmental biology, broadcasting, electronics, and a host of other subjects. At one point, Chip participated in UC Berkeley’s Prison Project, which in addition to helping incarcerated people with their reading and writing skills, also taught the principles of grant writing and public speaking. A top performer in the program, Chip’s Berkeley associates encouraged him to pursue a degree in Communication Arts and for many years they supported his endeavor in this area. A Jazz enthusiast, Chip also worked as a DJ for prisoner-run radio stations. In the process, he received a number of laudatory citations for good work and exemplary behavior in the performance of his prison duties. A self-taught and avid reader in the disciplines of history and the social sciences, Chip evolved into an unofficial educator inside the prison and to date he has mentored scores of young people, many of whom have left prison and continue to live productive lives.

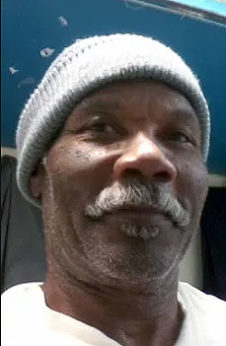

Imprisoned since age 20, Romaine has spent the last 51 years behind bars due to his wrongful and hurtful actions in the death of security guard Barge Miller. He is now 72 years old. He is the longest confined former member of the Black Panther Party and has been eligible for parole since October 1976. Having taken part in numerous therapeutic and rehabilitative programs, Chip has not made excuses for his past behavior and has consistently accepted responsibility for the irreparable harm he caused. Despite numerous visits to the parole board, he has been repeatedly denied a release date. Despite his overall good prison record, these parole denials have continued since 2004, when a Board of Prisons Psychologist examined Chip and determined that he was “at a low risk of committing offenses” if released. Statistics for released prisoners in Chip’s age group indicate that there is almost no chance that he would re-offend and be returned to prison.

In February 1998, Chip had a stroke that left him partially paralyzed and with limited use of his limbs. Rarely seen without his walking cane, he is currently housed in California State Prison, Los Angeles County, in the city of Lancaster, where he has encountered significant roadblocks in getting proper medical care. Chip remains hopeful that the state of California will forgive his past actions and accept that a fifty-year prison term is adequate payment of his debt to society. His hope emerges from the eternal spring all of us carry within us: a strong desire to enjoy the remaining years of life with friends and family.

Romaine comes from a good and respectable family, and his parents’ dying wish was to see him released from prison. Unfortunately, they both passed away years ago with this wish having gone unfulfilled. Chip now deserves a chance to exercise his human right to freedom and to engage his interests in constructive and positive ways. Having always been strong on the notion of family ties, after more than five decades, he still has hopes that he will one day be reunited with his son, 8 grandchildren, 2 great grandchildren, and 15 nieces and nephews.

IN PRISON 52 YEARS

52 YEARS IS ENOUGH!

SOURCE:

panthershepcat via groups.io <panthershepcat=aol.com@groups.io>

Mon 3/29/2021 9:28 PM

Replies